At my voice lesson yesterday, I was reminded why I am so bothered by the notion of “covering” a song. Having grown up in an era when this concept did not exist (and don’t aske me about the dinosaurs), I get agitated when I hear it used. In this instance, my voice coach thought my ‘cover‘ of James Taylor sounded nice. It came across to me as a mild insult, as if the speaker is saying that the original was better, and that the current performer is only purveying a less worthy and derivative copy, and does not have the skill to write their own material. She meant only good things by it, but still.

After going through a variety of Interweb sources that claimed to know the difference between “covers,” “remakes,” “remixes,” “interpretations,” and so on, I concluded that this term is not well defined. Some sources claimed that there was a more precise definition but others did not, and there was no authoritative source for the meaning. The Merriam-Webster online dictionary has 16 definitions of the word ‘cover’, the last of which is “to perform or record a cover of (a song),” which uses the word cover to define itself. Just not helpful IMHO.

The Online Etymology Dictionary shows many meanings of ‘cover,’ both as a noun and a verb. The earliest is to protect or defend or dissemble, from the 15th century French couvrir. Other early uses include to hide or screen (from c1400), or to aim at (from 1680), or as a euphemism for to copulate with a horse, from the 1530s. Oops! Sorry, I should have told you to look away before I said that last one about the horse. Just be thankful that you don’t live in the 1530s.

The meaning cited by the Online Etymology Dictionary that I was interested in was “to record a song already recorded by another” and dates it to around 1970 according to this dictionary. In 1981, the term “cover band” is cited to mean a band that only plays cover songs.

I found that a Professor of Philosophy at SUNY Albany, P.D. Magnus, who specializes in the philosophy of music and art, has written an entire book about the philosophy of covering songs. It is titled “A Philosophy of Cover Songs,” published in 2022. He has done a lot more research on when and how people started using the term “cover” to mean a song. After reading a good bit of it I had to stop, look up, and slap myself in the face. Basically, TMI. The arguments also reminded me of my college philosophy classes, which I have been trying to forget ever since I took them.

Magnus’ first chapter pretty well describes all the ways in which the term “cover song” is not well defined, and when you look at popular references to songs that people claim are covered you realize that, like time travel, the more you look into it, the more paradoxes you discover.

For example, John Lennon and Paul McCartney wrote “Let it Be” with the intention to record it, then sent a demo tape to Aretha Franklin. Franklin recorded the song and released it in January 1970. Two months later, in March, the Beatles recorded their version. So the Beatles version is a cover of an Aretha Franklin recording. But seriously, is it? (In case you are curious, here is the Franklin version – which I like a lot: https://tinyurl.com/yzekbtbc.

The last paragraph of Magnus’ book gives up, concluding that we are left with listening to music. I have to say that I liked the ending.

Professor Magnus actually provides one enlightening tidbit, which is that in the 1950s, music recording and promotion was in its early stage, and just starting to figure out how it fit into the world of publishing sheet music and live performance. The focus prior to this time period was generally on the song, and not the artist or performance as it is now. A frequently performed and popular song would become a “standard,” where sheet music would be widely distributed for people to play on their own pianos or whatever.

When an artist would stamp a recording under a small label, the larger ones realized that they could record the same “standard” and distribute it much more widely than the tiny company, making lots of money otherwise not being made by the competitor. This practice was known in the music production business (although not in popular culture) as covering the original song. It no longer means that, but at least this sense of the word was pretty clear.

So what is the difference? Otis Redding wrote and recorded “Respect” in July, 1965, but this song became famous only when Aretha Franklin recorded and released it in 1967. Most of the references to both say that she covered it. The website “secondhandsongs.com” has a list of 111 covers of this song, including two by Aretha Franklin herself. My favorite one that is not by Franklin is this:

Why don’t we refer to the Beatles version of “Twist and Shout” as a cover, as they did not write it, nor were they the first to record it? When a band performs their own songs at a live concert and it is recorded for an album, are they covering their own song? If a band plays only their own songs that they have previously recorded, are they a cover band?

The Top Notes version of Twist and Shout was the first version to be performed and recorded in 1962 of the song written by Bert Berns and Phil Medley in 1961. Phil Spector produced it, but Berns hated the recording. Here are the Top Notes with Twist and Shout. You can decide for yourself where the Beatles version sits vis a vis cover or not: https://tinyurl.com/4jk5wr49. Like Bert Berns, I hate this recording.

So Berns produced his own version, performed and recorded by the Isley Brothers. This one sounds a lot like the Beatles, albeit the tempo was just a tad slower. The Beatles loved the Isley Brothers’ version and largely copied it. The call and response part is there, which is what makes the song fun for audiences. The call and response emphasis probably reflects the fact that the Isley Brothers were Black and grew up singing in church. I recommend that you go to youtube and listen to the Isley Brothers’ doing this song. You won’t regret it.

Let’s explore this with one of my favorite classic songs covered by a rock band. I’m talking about the fifth movement from Bach’s Suite in E Minor for Lute. The movement is titled “Bouree” in the Bach manuscript because a bouree was a popular dance in Europe at the time, and this movement was intended to echo the dance.

We can’t know what this would have really sounded like when Bach’s contemporary musicians played it, but here is Evangelina Mascardi playing movement #5, the Bouree, on a baroque lute, so it should be very similar to the original:

Note that this song includes both a melody and a counter-melody. Ms. Mascardi deftly plays both concurrently, as written in the OG (the original). Here now is Italian Marcin Dylla covering the song on a modern classical guitar :

Note that Mr. Dylla adds a lot of ornamentation after the repeat which was not present in the Mascardi rendition. Does this make it any less of a cover? Which one of them has the more authentic interpretation? If you add notes and ornaments, does that affect how much of a cover it is? These are extra credit questions.

And finally, here is Ian Anderson and Jethro Tull, also covering the song in a studio recording:

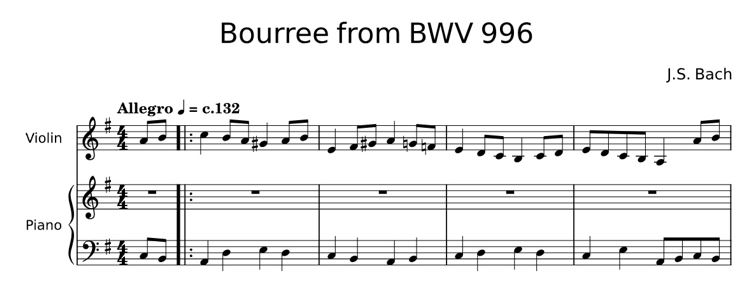

Note in particular that Martin Barre, Tull’s guitarist, plays the counterpoint to the bouree melody as if he were the left hand part of the Bach version. It’s a bit of an improvisation as far as I could tell from following along the Bach sheet music, but hey, it’s a cover. You can follow along with Martin Barre on the opening by reading the first line of the Bach as Jethro Tull plays the same bit:

The Green Bean Casserole Cover Experiment

Let’s put the notion of “covering” an artistic creation into another context to better see why the idea of “covering” a song rubs me the wrong way. I have selected recipes as that other context.

When you cook spaghetti and meatballs according to a recipe you get from Martha Stewart, no one would say that your dish is a cover of Martha’s, or that you are a cover chef if you don’t invent your own recipes. The word ‘cover’ just not necessary, and everyone understands that there are ingredients for food which anyone is welcome to mix up and prepare to their own taste. It is customary to start with an idea for a recipe that someone else has published or made famous. You can prepare it just as the published version calls for, or you can change it up a bit.

For example, when you make the Campbell’s recipe for Green Bean Casserole, which is famously printed on the back of cans of Campbell’s Condensed Cream of Mushroom soup, no one would say that you are covering the recipe. Would they?

Thinking about this inspired me to try out a batch, to see whether my casserole felt like a cover of the Campbell’s recipe or not.

The first step was shopping for the ingredients.

The recipe calls for two cans of green beans, one can of Cream of Mushroom Soup, and a can of fried onions. (I had never heard of fried onions in a can, nor could I recall eating green beans from a can. I was willing to make the sacrifice for the sake of attempting to cover the famous Green Bean Casserole.) Whoa — these cans were all in the same aisle! Aisle 2! I had been to this aisle before. I felt that to be a good omen for the project.

Here are the ingredients:

I think the can sizes have gotten smaller since my Mom used to make this stuff, but I could be wrong. Perhaps I have gotten bigger. You also need a small amount of milk, a little soy sauce, and finally salt and pepper. For extra Campbell’s goodness, you can add cheese and bacon crumbles. I stuck with the basic recipe to keep my recipe cover experiment authentic. After 35 minutes in a 350 deg. oven, here was the result:

I would say that this casserole looks a lot better than it tastes. If I had it to do over, I would add the cheese and bacon, and use fresh beans instead of the cans. I think the fresh beans would be the key to a better cover for this recipe, and the cheesy bacon might help to drown out the beans. The onions were crispy and delicious. The soup is neutral, gluing it all together.

This recipe was invented in 1955 by a Ms. Dorcas Reilly, an employee of Campbell’s in Camden NJ where she was the supervisor of their Home Economics department and test kitchen. The dish was inexpensive, easy to prepare, quick to bake, fed a family, was crunchy and tasty, and used ingredients that most households at the time would already have in their pantry. In other words, a perfect post-WWII invention for families where mom just got her first job outside the home. Ms. Reilly died in 2018 at age 92, bless her heart, of Alzheimer’s. Campbell’s has estimated that 40% of all sales of their Cream of Mushroom soup go towards making the Green Bean Casserole, and that the recipe is prepared in 20 million American households each Thanksgiving.

What was my conclusion regarding whether I had ‘covered‘ the recipe? Well, I definitely prepared the recipe. The word cover would have added no information that you did not already know, based on my telling you that I was making Green Bean Casserole. So I say we don’t need to use that word in the context of recipes.

Getting back to my reaction to the concept of covering a song, I feel the same about song covering as I do about recipe covering. Calling it a ‘cover‘ adds no useful information. And, it seems slightly condescending. If I tell you that I sang at Karaoke night, it adds nothing to say that I covered the songs. You already know what happened (which was that I sounded slightly amateurish but sweet and vulnerable), and that I did not write any of the songs. Or that the Karaoke machine recordings were covers. You already know what they are. Likewise, to say that Jimi Hendrix ‘covered‘ the National Anthem at Woodstock in 1969 is not helpful. He shredded it.

Listen for yourself; let me know if you think this performance was a cover or a shred. Or something else entirely.

Jimi at Woodstock – https://tinyurl.com/y2kayb7k.