Breaking News! I know you have been on the edge of your chair waiting for this one! I liked this story because it is full of interesting twists and turns about a law I had never heard of that could place requirements on me, taking me down various rabbit holes some of which I will elaborate below.

The Fifth Circuit Federal Appeals Court this week upheld a stay on the Corporate Transparency Act, or CTA. The CTA went into effect in January 2024 and was to start enforcement this January 13th, 2025. The CTA requires that nearly all small businesses file a one-time form indicating who owns the company, with an update whenever ownership changes. This is to prevent money laundering, which the Treasury Department feels is widespread, and which Congress has determined to be bad. Often, identifying money laundering is a way to spot people committing other, even more serious, crimes.

For example, a criminal with illegal income will set up a legitimate business whose income includes a substantial amount of cash. Examples include restaurants, casinos, betting parlors, really any retail establishment, especially before the widespread use of credit cards, and of course laundries. Once deposited in a bank account, both the legal and the illegal money can be spent as if you earned it legitimately. These days criminals will usually move it around to other accounts, often under anonymous ownership, until finally they invest it in something legit, like a mega-yacht or a big real estate deal. I’m sure you get the idea.

The Center for Individual Rights or CIR (a libertarian/conservative advocacy law firm) brought a lawsuit in the Federal Eastern District of Texas claiming that the Government does not have the Constitutional authority to impose this law. The Government won in the east Texas Fifth Circuit Federal District Court, leaving the law intact, but an appeals court panel of the Fifth Circuit this week reversed the ruling, agreeing with the Center for Individual Rights. This resulted in a stay of implementation of the law. A stay is where the court suspends implementation of a prior ruling, in this case for the indefinite future. So for now, the Treasury Department is not enforcing the CTA although the law is still in effect.

Why does an individual have a right under the constitution to illegally launder money, or more directly, to hide money from the Government under the wording of the Constitution? I don’t recall this clause. Critics of the law feel that the reporting requirements will be too onerous, which is an entirely different argument. Are they correct? It’s not at all clear to me. You file a form once, and then are required to report changes in ownership as they occur.

There is ample precedent for rulings on this argument, all of which affirm that Congress does, indeed, have the authority to regulate business in accordance with the language of the CTA.

The penalty is stiff for non-compliance, which makes sense because the targets are criminals who generally would just ignore the law. They are criminals, after all, who are laundering money illegally; why should they turn themselves in by filing a CTA form? Penalties include a large fine – up to $10,000, a two-year jail sentence, and last but not least, the Government can take the property which it determines was obtained illegally as a part of the money laundering scheme. Yikes. Say goodbye to your mega-yacht or your mansion in Malibu.

Here is Fifth Circuit Appeals Judge Mazzant’s argument in halting the enforcement of the CTA: the Commerce Clause of the Constitution (article 1, section 8) allows the Federal Government to regulate interstate commerce. It is an enumerated power of Congress, meaning that the Constitution mentions it specifically. However, the CTA law regulates a small business without regard to whether they are engaged in interstate commerce. Which is not the thing that is enumerated. Case closed!

This sounds like a clever argument, as the commerce clause was narrowly interpreted when written, but has gradually become more broadly interpreted over time by the courts. If all your clients are local in, say, New Jersey, would Congress have the authority under the interstate commerce clause to regulate the business? (A related question: why are there interstate highways in Hawaii?) Unfortunately for the Center for Individual Rights, this argument has been made before many times, and the courts have uniformly ruled that yes, the Government does have this authority under the Constitution.

So when did “money laundering” become illegal? Hasn’t it always? Well, no, it hasn’t. The first US law intended to be ‘Anti Money Laundering’ (or AML) was the 1970 Bank Secrecy Act, or more technically the Currency Reporting and Transaction Act of 1970. This requires that banks and other companies report cash transactions over $10,000 to the Treasury department, and also file reports whenever something looked suspicious. The reports need to include who the parties were who made the transactions. This has been one of the most fundamental tools used to combat illegal money laundering, although it did not make laundering of cash per se illegal but was essential in identifying the criminals so that they could be pursued under other laws. If you are feeling the need to launder money, then you have probably obtained that same money under illegal circumstances, which you could be thrown in jail for.

The next big legislative milestone was the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986. This kicked things up a notch by making money laundering, or knowingly disguising a financial transaction in order to hide illicit funds, a Federal criminal felony, with up to $5,000,000 in penalties, up to 20 years in jail, and potential forfeiture of the asset. I’m simplifying, but you get the idea.

There have been six major additional laws passed that strengthen the first two in a variety of ways. These include the USA Patriot Act which, in response to the 9/11 terrorist event, added that money laundering can be prosecuted as an act of terrorism under certain conditions. And five more.

FinCEN, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, is the entity within the Treasury Department charged with enforcing the various money laundering laws passed by Congress.

In order to make this arguably esoteric subject more concrete, I did some research to find notable enforcement actions by FinCEN against violations of these laws. I came up with a doozy! Here is an excerpt from a FinCEN public news release dated March 6, 2015:

“The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) today imposed a $10 million civil money penalty against Trump Taj Mahal Casino Resort (Trump Taj Mahal), for willful and repeated violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). In addition to the civil money penalty, the casino is required to conduct periodic external audits to examine its anti-money laundering (AML) BSA compliance program and provide those audit reports to FinCEN and the casino’s Board of Directors.

Trump Taj Mahal, a casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, admitted to several willful BSA violations, including violations of AML program requirements, reporting obligations, and recordkeeping requirements. Trump Taj Mahal has a long history of prior, repeated BSA violations cited by examiners dating back to 2003. [emphasis added] Additionally, in 1998, FinCEN assessed a $477,700 civil money penalty against Trump Taj Mahal for currency transaction reporting violations.

“Trump Taj Mahal received many warnings about its deficiencies,” said FinCEN Director Jennifer Shasky Calvery. “Like all casinos in this country, Trump Taj Mahal has a duty to help protect our financial system from being exploited by criminals, terrorists, and other bad actors. Far from meeting these expectations, poor compliance practices, over many years, left the casino and our financial system unacceptably exposed.”

Trump Taj Mahal admitted that it failed to implement and maintain an effective AML program; failed to report suspicious transactions; failed to properly file required currency transaction reports; and failed to keep appropriate records as required by the BSA. Notably, Trump Taj Mahal had ample notice of these deficiencies as many of the violations from 2012 and 2010 were discovered in previous examinations.”

This press release was from 2015, but the Bank Secrecy Act had stalked Mr. Trump from the outset. This is from a May 22, 2017 CNN investigative article resulting from journalist Jose Pagliery digging into the records: “The Trump Taj Mahal Casino broke anti-money laundering records 106 times in its first year and a half of operation according to a settlement with the IRS,” he states. To prove that I am not making this up, this link goes to the Government web site with a copy of the settlement agreement:

Notable in this agreement is a) Trump’s casino admitted that they violated the Bank Secrecy Act 106 times while simultaneously claiming that they did nothing wrong, and therefore bore no responsibility; and b) the Trump casino nonetheless agreed to pay a $477,000 penalty.

In one final ironic gesture, during his 2024 campaign for President, Donald Trump compared himself to Al Capone. I’m not making this up; you can Google “Trump compares himself to Al Capone YouTube” if you don’t believe me, which, frankly, I wouldn’t have believed it if I had not seen it. His intent, I think, was to say that he was even tougher than Capone by virtue of being indicted more times than Capone was. Because the number of indictments thing is not true, the claim to be tougher than Scarface falls a little flat for me. One thing is evident, which is that Al Capone made millions of dollars from illegal criminal enterprises, and found creative ways to “wash” the money so that he could spend it tax-free on lavish perks while murdering people who got in his way.

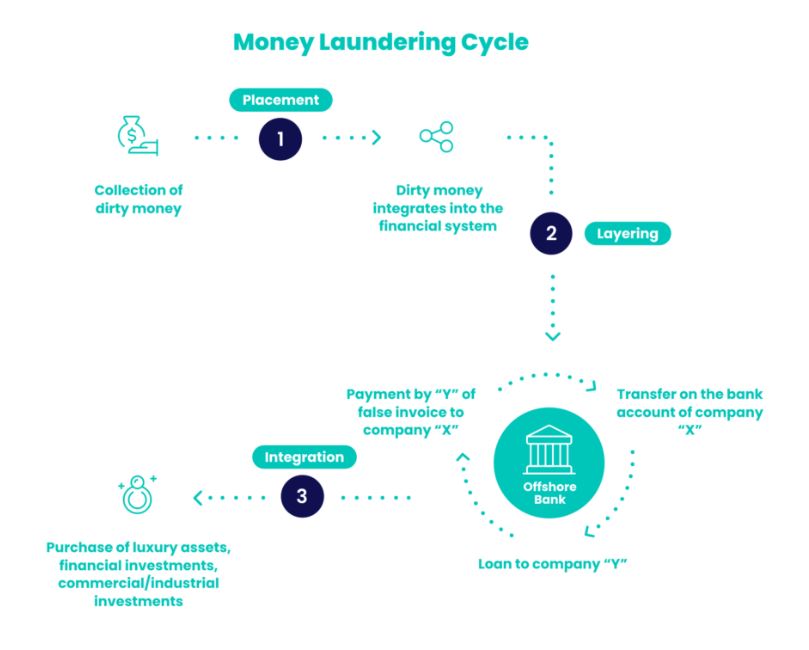

According to the US Treasury department, there are three basic phases to money laundering:

- Placement, or the introduction of illicit funds into the financial system

- Layering, or the use of a series of processes to hide the true source and ownership; and

- Integration, activities to make the funds indistinguishable from legally obtained money.

Here is a diagram showing this:

The Treasury Department estimated that laundered money in the US is upwards of a $300 billion annual marketplace. That money represents a lot of crime, which hurts many Americans.

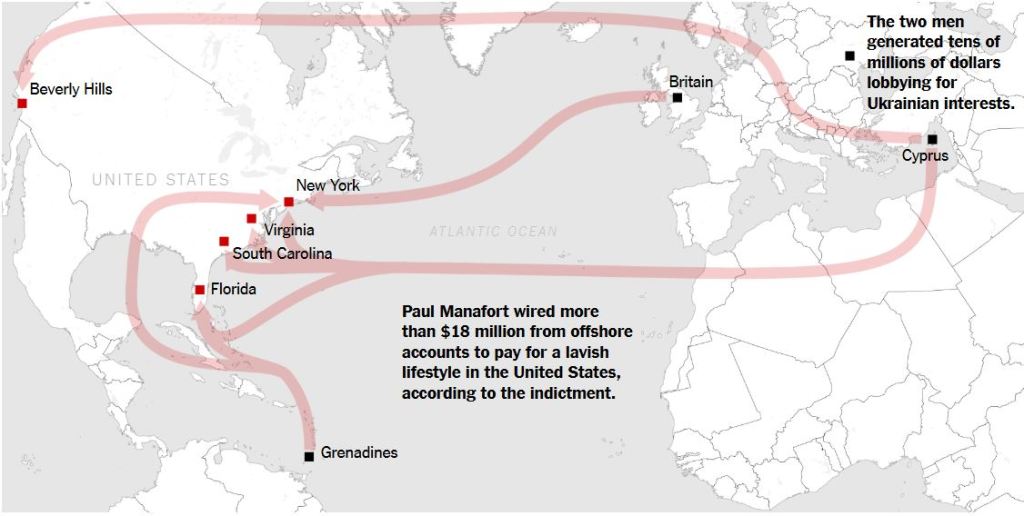

I found a real-life example of shell companies and related techniques to hide money in violation of the Bank Secrecy Act. After searching for the “10 biggest money laundering schemes in history,” Paul Manafort’s name popped up. This link, https://tinyurl.com/yewmphvx, points to the text of the Federal indictment of Manafort and his partner Richard Gates, who carried out the laundering and bank fraud scheme.

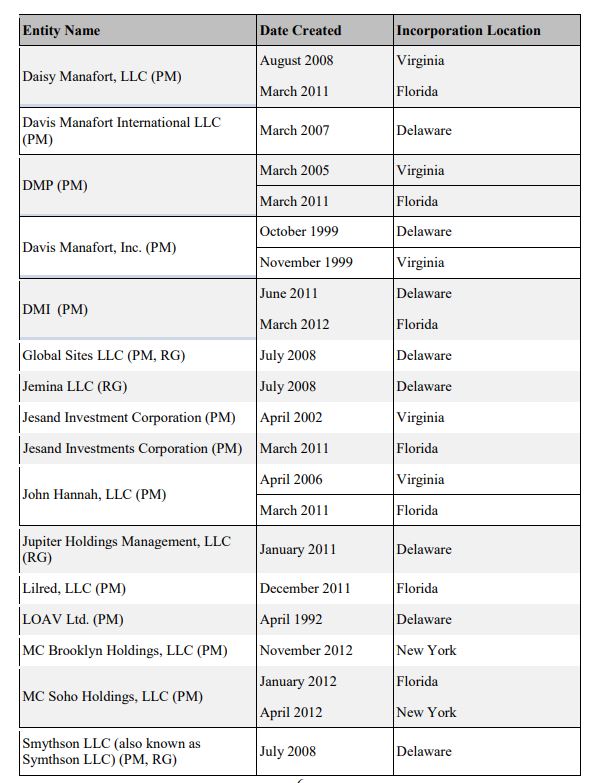

Next is a table from his Federal indictment for violating the Bank Secrecy Act highlighting some of the shell companies that he set up in order to move millions of dollars so that the source of the funds would be harder for the authorities to find:

Clearly the shell company subterfuge did not work. Oops! As far as I could tell, Manafort’s partner ratted him out, and then Manafort himself sung like a canary.

The scheme’s purpose was to hide funds paid to Manafort by a Ukrainian politician, described as a “Putin Puppet”. This was Viktor Yanukovych, who was forced to flee to Moscow in early 2014, only escaping with the help of a Russian army air transport in Crimea. According to the indictment, the total amount of money laundered by Manafort and his partner was around $30 million. During the time that he was conducting this money laundering scheme, Manafort signed on as Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign chair. In addition to advising the candidate, Manafort also spent some of this money lobbying the US Congress for the interests of the Ukrainian government without registering as a lobbyist. This is a pretty blatant conflict of interest, which is why it initially came to the attention of the authorities. Manafort was found guilty and spent two years in jail for his crimes, and would have languished even longer except for the fact that he received a full pardon from then President Trump.

In any event, the Corporate Transparency Act had not been passed when this all occurred, and so it is not clear whether it would have been needed to root out the $30 million in laundered money. But it couldn’t have hurt. I will keep alert for further developments in the saga of the Constitutionality of this law. That’s it for now.