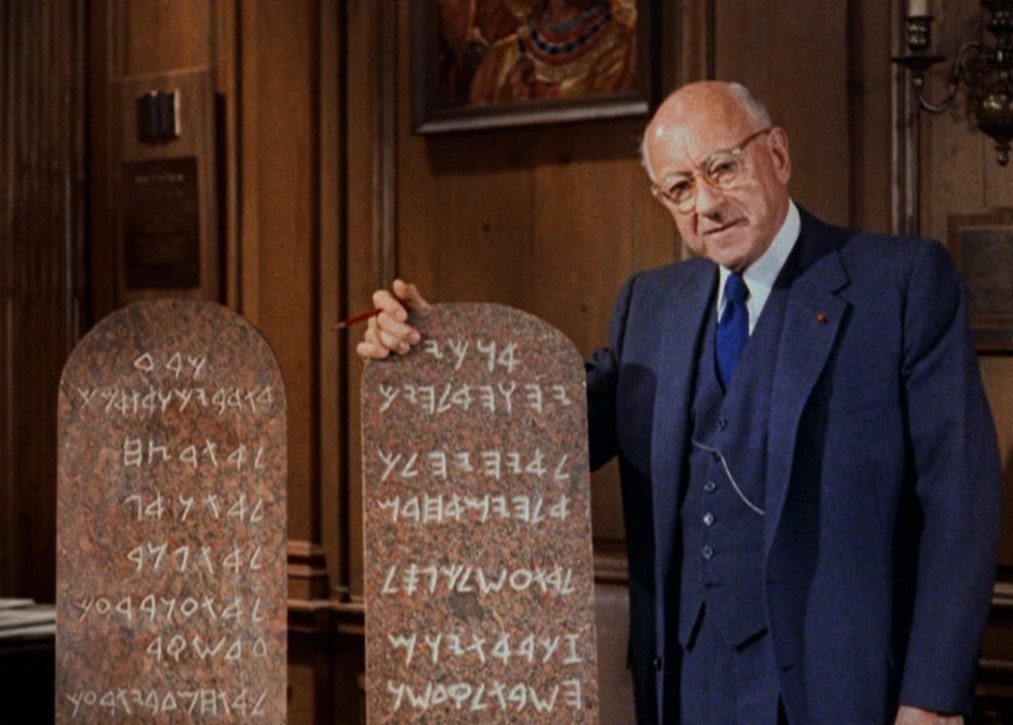

In the news today the governor of Louisiana, Jeff Landry, just signed a law (H.B. 71) requiring that every public school in the state display a copy of the Ten Commandments. The display must be at least 11 x 14 inches; the new law allows for the display to optionally be paid for via donations so that the law is not an unfunded mandate. Legislators included a carve-out in the bill for private (i.e., Christian) schools, which are not required to post the Bible passage in their classrooms because, I don’t know, perhaps they didn’t want to be told what religion to practice. The specific wording of the commandments is spelled out in H.B. 71, and has to be exactly as follows:

“I am the Lord thy God.

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven images.

Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.

Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy.

Honor thy father and mother, that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

Thou shalt not kill.

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Thou shalt not steal.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.”

Notice that there are actually 12 commandments listed as required by H.B.71. There would be even more if you made the elements of the lists into their own declarations. The King James Version of the Bible in Exodus 20 lists 16 declarative statements, including a little bit more context for a few of them, such as a prescription on doing any work on the Sabbath, the addition of a few more farm animals, additional references to servants (which, like the man- and maid-servants were likely slaves when this was written) and so forth. You are probably asking yourself at this point why the legislators of the State of Louisiana thought that their citizens still owned slaves. It’s a good question.

One more note about the King James version; it is a translation that is in the public domain and therefore you don’t have to pay royalties to a publisher for each copy. This would have added up when you consider that the posters are required in every single classroom of every single public school – up through college – in Louisiana. It is a translation that is less authentic to the original Hebrew text than most others, but evidently this aspect is secondary to the authors of H.B. 71.

There are three different places in the Christian Bible where the commandments are expounded: Exodus 20, Exodus 34, and Deuteronomy 5. Each is unique, although there is some overlap regarding adultery, killing, stealing, bearing false witness, and holding the Lord as the one true God. (Exodus 34 seems to be the outlier, mostly dealing with rules regarding ritual Jewish animal sacrifice.)

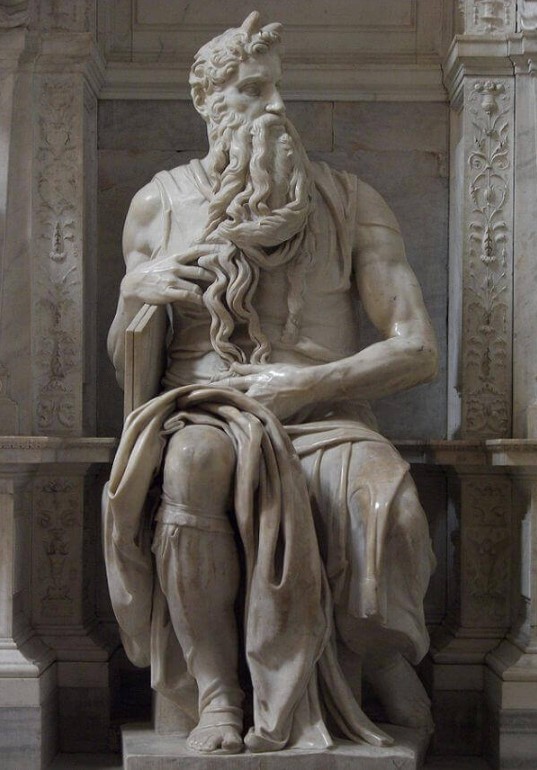

The Ten Commandments as commonly understood here in the US are in two parts: part one concerns each person’s relationship to the Lord God, and part two concerns each person’s relationship to others. In our Western culture, the Commandments were among the very first statements defining the notion of the rule of law going back as far as 1500 BCE. They were a huge step forward from “the tribal chieftains decide what to punish,” where every tribe has their own rules based on preferences and whims of the elders.

Some of these commandments tell you not to do things that are already currently illegal, so perhaps these could have been omitted from the Louisiana law. For example, stealing: illegal. Killing: illegal under certain circumstances. Bearing false witness: illegal, when it leads to harm, although “little white lies” are fine, as are many other exaggerations or intentional misstatements.

On the other hand: adultery, not illegal, at least not in Louisiana. Graven or molten images: fine. Actually, not a thing. Swearing, if a reference to God is included: fine, normalized and encouraged. Coveting: fine, and it forms the basis for our modern American system of free enterprise and marketing. Dishonoring father or mother: not illegal, but discouraged. Working on the Sabbath day: What? Fine. Worshipping deity other than Judeo-Christian God: fine, for instance in New Orleans, the part of Louisiana where things like Voodoo and Santeria are accepted religious practices.

Does this mean that as Americans we have strayed from our ethical roots? It might. Or, it could just mean that our culture has evolved in the last 3,500 years to where our laws don’t have to be so blunt, don’t have include farm or pro-slavery references, and are now tailored to and better suited to what life is really like in Louisiana in the 21st century.

In the Biblical New Testament, Jesus is asked which of the commandments he considers to be most important. In Matthew 22, he strips the 10 down to just two:

“‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

If I were posting Biblical commandments on the walls of elementary schools, I would just boil it down to these two. I think they are clear, relevant, and actionable. And very religious.

The authors of the Louisiana bill claim that, while HB 71 is “slightly” religious in nature, it is primarily a historical document of great significance to the founding of the country. The law was amended to respond to some criticism that H.B. 71 was too overtly religious; it now includes references to other historic documents, such as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, although none of these other ones are required to be displayed in every public school classroom.

So, like me, you are probably wondering: “What is this historic Northwest Ordinance of 1787?” The ordinance was drawn up to define the rights of the people and territories north and west of the Ohio River, which area is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Think Northwestern University. The ordinance included the right to representation, but only for non-enslaved and non-female residents. It included the freedom to practice the religion of your choice (which would seem to be antithetical to posting the Christian Ten Commandments in every public school classroom). It was enacted by the Congress of the Confederation of the United States, an entity that was dissolved and obsoleted just one year later in 1788 by the US Constitution. The Louisiana legislators are correct in identifying this as a document in the history of the US since it laid out the methods and procedures for territories not in the original 13 to become states. It did not make any reference to the Ten Commandments.

Where is this blog going? Feeling a bit lost, I am now going to take it back to the root of the separation of Church and State in America. And even before Thomas Jefferson, who famously used the “wall of separation” phrasing in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Connecticut Baptists. No, before this it was Roger Williams (1604-ish to 1683) who set the tone for religious freedom in the early colonies.

Williams was a Puritan, and came over from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s, eventually to become a Puritan minister. The Puritans were strict about having a civil government that enforced what they felt were their Christian values and beliefs, effectively turning these beliefs into covenant laws. After experiencing disagreements with the colony elders regarding the entanglement of the State with the Puritan Christian church, Williams was banished in 1636 to what is now Providence, Rhode Island, and in the 1640s went back to England to obtain a Royal Charter for his new home, making Rhode Island a haven for religious freedom, a British Colony, and eventually a US State.

Unlike Jefferson, Williams’ primary concern was not that the Church would corrupt the government, but that the government would corrupt the church. Williams thought that if church elders were given civil authority that it would lead to abuse of the type that had occurred in the Church of England (which he felt was beyond redemption), as well as in the European Catholic Church prior to the Protestant Reformation.

As a reminder, Protestants split from the Catholic church in large part because the Pope was taking payments for telling people that their sins were forgiven, or that their route to heaven was assured, or that they had paid their way to one form or another of saving grace. This was called “selling indulgences.” It was widely considered to be a corrupt practice, in that the Pope saw it primarily as a source of income for use in plundering the believers.

Although the Puritans are often thought to have come here to escape religious tyranny, in fact they set up a theocracy that was just as tyrannical in its own way as the Church of England, with no tolerance for dissent or acceptance of other religious beliefs, even (or especially) other Christian denominations.

Williams best documented this in a book published in England in 1644, “The Bloody Tenet of Persecution for Cause of Conscience.” He coins the phrase “wall of separation between Church and State,” and argues from the text of the Bible that the Church should not have civil governmental authority. He understood how easy it was for church elders to take advantage of the parishioners to the detriment of the spiritual mission of the Church.

Here is an additional note regarding the Puritans, who Williams felt invited corruption through entanglement. Puritans form the basis for the society depicted in Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” which I have already commented on at some length. In that book, the founding fathers of a religious nation start off with the best of intentions, but inexorably are led down a path of theocracy, corruption, and harm to the citizens. The result is a religious dystopia where everyone is ultimately stripped of their freedom and free will, despite this not being the intent of those who set up the government.

Coming back to Louisiana, the Governor and others who passed H.B. 71 requiring the entanglement of Church and State have the best of intentions for the people. After all, how can it be bad to expose children to the Ten Commandments? Are these commandments not the foundation for our Christian values and the rule of law?

Yes, in a way they are. But the concern is really that we would lose sight of the lessons learned from the Puritans, the Church of England, and the European Catholic Church of the middle ages. This particular Biblical display is a small step down the path of integrating the Government with the Church. Perhaps it would be fine. But, if Roger Williams were alive, he would be concerned that the religious leaders are losing control, and that they would ultimately be consumed by the power they could wield over the people. The result would be a Church that has lost its way in guiding souls to heaven, as well as a government that would not serve the democratic interests of its people.