For the past few years, I inexplicably perk up whenever tardigrades are the subject of a news story. Perhaps you will understand when you see what they look like:

I know, you want to look away but you can’t. Here is a description of them, taken from an article last year written by Neal Patel of the Daily Beast:

“Tardigrades are some of the most compelling organisms to have ever evolved on Earth. Also known as water bears, these 1-millimeter long eight-legged creatures have been known to survive the vacuum of space, withstand boiling water for at least an hour, endure high amounts of radiation, and make it through unscathed from some of the most extreme colds imaginable. As a result, tardigrades have managed to find a home on nearly every place on the planet.”

Monday was “Earth Day” and the news that caught my attention was an article by NY Times science writer Carl Zimmer, who was also apparently fascinated by research about these cute little guys. He talked with Dr. Jean-Paul Concordet, a French researcher who recently co-authored a study about tardigrades’ ability to repair DNA after damage from ionizing radiation. Humans also have the ability to repair broken strands of our own DNA, but tardigrades manufacture the protein involved in the repair in prodigious amounts. Why do they do this? We don’t know. We do know that if we could replicate the tardigrade’s unusual ability to repair our own DNA, we could cure almost all disease. It would be a good thing.

Tardigrade’s mating behavior has also been studied. They are oviparous; that is, they lay eggs, like birds. Which they definitely aren’t. Boy and girl tardigrades need to mate for there to be babies, but the question posed by biologists in a paper published this past December was: How do the boys know which ones are the girls? They don’t have any sensory organs that anyone can find, nor are there any differences in how they look or behave. Challenge accepted by modern science! It turns out that they can smell the difference – even though they do not have noses. Justine Chartrain from University of Jyväskylä, Finland spent countless hours watching the tiny animals go after each other, setting things up so that it would be evident how they decided who was who. And it was the way they smelled. Those Scandinavians sure know a good time when they see it.

Here’s something you probably did not know: tardigrades are evolved from lobopodians. Lobopodians lived between 485 and 541 million years ago, aka the Cambrian Period. So, tardigrades have been on earth for around 500 million years, and have survived all five mass extinction events. I am not including a picture of any lobopodians because, frankly, they are ugly. Please don’t Google them.

According to Stephen Chen of the South China Morning Post in an article published in March 29, 2023, Chinese scientists have been inserting tardigrade DNA into human embryonic stem cells to see if they could create people who are resistant to radiation damage, just like the tardigrades. This would allow the Chinese army to be populated by “super soldiers” who are not susceptible to radiation from nuclear weapons. Chen says that they have achieved some success, at least at the level of human cells in a laboratory.

I think this was made into a movie – Jurassic Park? SpiderMan? The Hulk? I’m not sure which one, but I have only one question for those hard-working Chinese scientists: “What could possibly go wrong?”

Perhaps my favorite news story appeared in LiveScience in December, 2021 where a tardigrade was “quantum entangled” with a separate subatomic particle. Quantum entanglement was predicted by Niels Bohr in 1933 as part of the initial development of the theory of quantum physics. When two particles are entangled, a change to one will show up instantly as a comparable change to the other even though they are infinitely far apart in space. This means that the connection violates the cosmic law of the speed of light, or in other words, it violates Einstein’s theory of relativity. Einstein himself thought that quantum entanglement was impossible. Experiments since then have shown it to be a real thing, so I guess there is still a lot we don’t know about how the universe works.

Anyway, a group of eleven researchers headed by Dr. Kai Sheng Lee of Singapore took 3 tardigrades from a roof gutter of a university building in Denmark. (Tardigrades are common in moss and lichen, so gutters would be a happy place for them.) The scientists placed three of the little animals in the middle of a specially constructed electrical circuit and froze the assembly to less than one degree above absolute zero (or -459.67 deg F), with the tardigrades attached to one of two entangled subatomic particles. At this point, the tardigrades were technically dead. When one of the particles was “nudged” (vibrated?), the tardigrade and the other particle changed its resonant frequency, showing (in the words of the researchers) that the tardigrade was entangled. Then, after the tardigrades were slowly restored to room temperature one of them returned to life! (Oops- the other two died.)

I really have no idea what this means, other than these guys really had some fun with tardigrades in a very serious refrigerator.

Of course I had to see if I could find some tardigrades and examine them for myself. This part turned out to be a bigger and more frustrating project than I expected, and I have spent considerable hours this week scouring the area for moss and lichen, and then attempting to find a tardigrade in a microscope in my kitchen. Science experiments sometimes fail. I fired up the Internet and watched several videos explaining how easy it would be to gather them from your own backyard and see them in your kitchen.

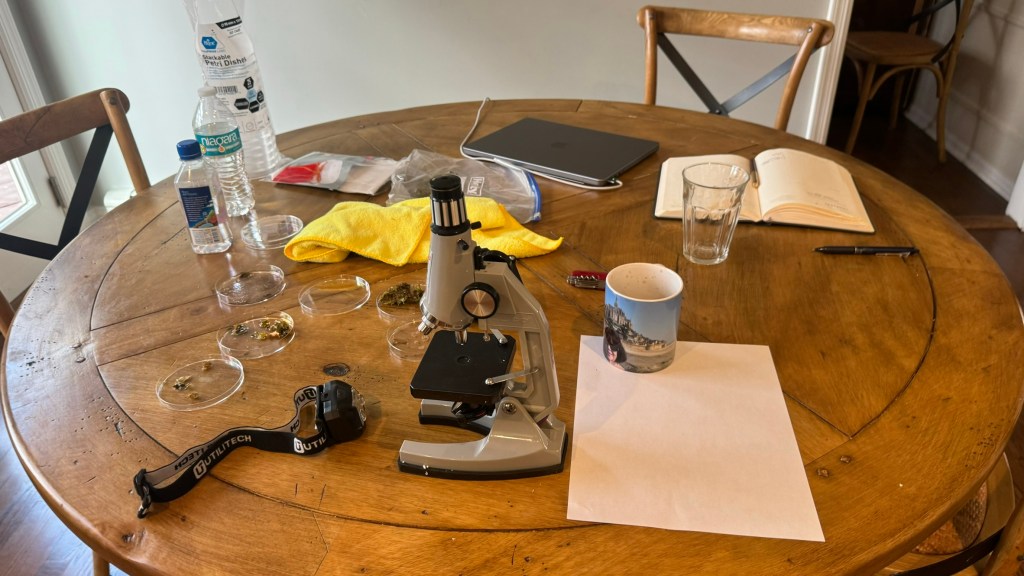

The videos listed what equipment is needed: a microscope, petri dishes, a pocket knife, and bottled water. After ordering the petri dishes from Amazon and borrowing a microscope, I was set. Here is a picture of my lab:

Next, I gathered moss and lichen from nearby trees. I did this every day for four days, each time from different trees, starting with the maple tree in my backyard, then a nearby creek, and eventually going to a local county park.

I’m not sure that you are allowed to remove moss and lichen from trees in a county park, but I did this at a quiet time and I’m pretty sure that no one saw me do it. Here is what one of the trees looked like, and you can see both the moss and some lichen:

I ordered the petri dishes on Sunday and they arrived Monday (and thank you very much Amazon Prime). You are supposed to soak the moss for between 4 and 12 hours (depending on which Internet video you believe), then squeeze the wet material into a sterile petri dish where you might find a tardigrade.

In my case, on Monday: Gathered moss and lichen from my yard, let them soak. No tardigrades.

On Tuesday: again, no tardigrades. Back outside to look for better trees, this time in a neighborhood creek.

On Wednesday: and again, no tardigrades. Back outside to look for different and yet better trees, this time in the county park. I was becoming discouraged. Did I mention that in science, experiments can fail?

On Thursday: I saw a tardigrade!

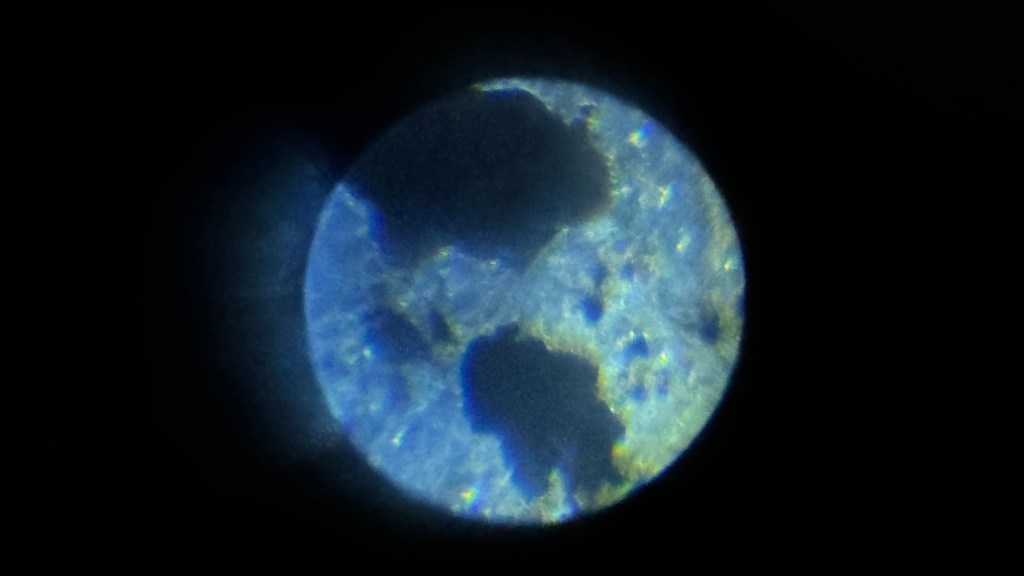

Unfortunately, I was not able to capture a photo of the one I saw. It kept moving around. Here is the best I could do to capture the sort of thing visible to me in the microscope:

My view was not this blurry, but the 1990-era microscope was not designed to connect to an iPhone camera so this is the best I could do. I think the picture looks rather like a view of Australia from space, but you will have to use your own imagination.

Someday I hope to introduce my grandchildren to the fantastic microscopic world of tardigrades. They may hold to key to our species survival.