Today is another OMG! story! Last September I noticed that my Medicare statement included a payment to a “Royce Medical Supply LLC” for 400 intermittent sterile catheters. Which I don’t use and did not receive. These were ordered in bulk, totalling almost $4,000 which Medicare had already paid to Royce. (I’m not going to explain what an intermittent catheter is; you can look it up.) I immediately called the Medicare Fraud number and had a long conversation with a nice agent who told me that she would sent a note to someone about it, and agreed that, yeah, it kind of sounded fraudulent. I then called UnitedHealthcare, my supplemental insurance provider, who said that Medicare had approved the payment, but that she would also send an appropriate note to someone else in the company. I was told by Medicare that people who report fraudulent transactions like these don’t get any follow-up notification, and I hadn’t heard anything about it since then.

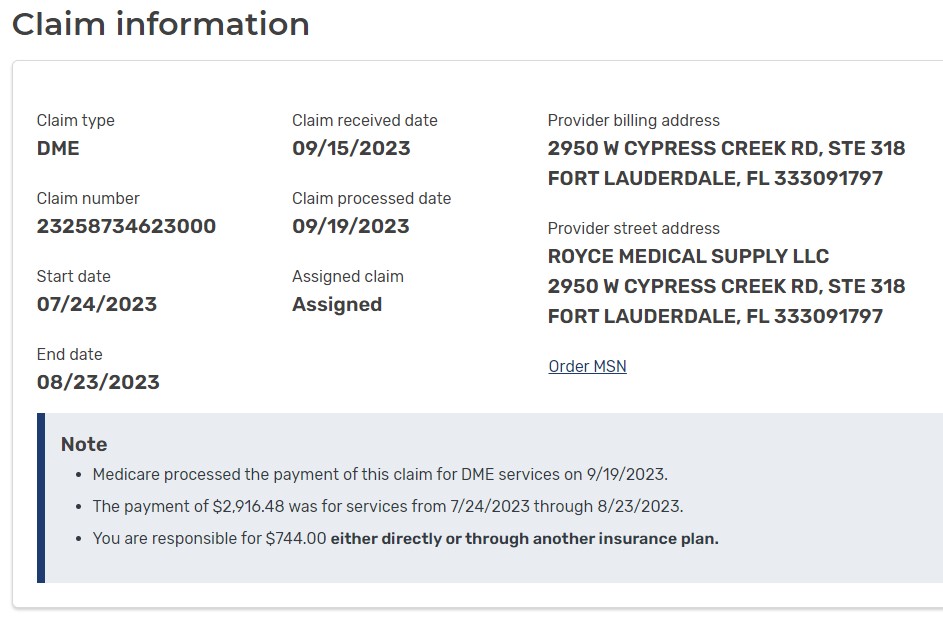

Until this morning. Here is a screen grab from my Medicare statement:

Both the New York Times and the Washington Post today reported on a fraud investigation underway involving Royce Medical Supply at the exact same address in Ft Lauderdale that showed up on my catheter order, 2950 W Cypress Creek Rd. What’s more, this is the biggest fraud ring that has ever been pursued on behalf of Medicare, amounting to about $2 billion in total fraudulent payments. There are alleged to be seven companies in the crime ring and they all billed for bogus intermittent catheters, apparently because this is something that typically does not get much attention by the Medicare auditors.

Although in this case, the giant spike in one product, all from a small select handful of companies, should have raised some eyebrows at the Medicare fraud desk. Especially given that I can’t have been only one to notice, although I will say more about this later.

The pattern seems to have been that the criminals legitimately purchased companies that already had licenses to bill Medicare for durable medical equipment, referred to in Medicare lingo as DME. Every company involved in the scheme was purchased in 2023 after being run legitimately before then. This avoided red flags based on the billing service provider, and gave the gang access to Medicare’s billing system.

How they obtained my Medicare ID and related information is a mystery. I had not done business with this company, or any of the seven, so they didn’t get my name from their own records. They must have stolen my Medicare ID, or obtained it from someone who did.

The Washington Post journalists interviewed Dara Corrigan, the head of the Medicare Fraud Prevention group. Corrigan declined to give any specifics regarding the state or scope of the investigation, stating that divulging any information might compromise an investigation that might or might not be ongoing. Ditto for FBI.

According to the Post, “The alleged scheme was uncovered by the National Association of ACOs (Accountable Care Organizations).” NAACOS is a non-profit trade group that represents hospitals and providers across the country. This role gives NAACOS access to Medicare records that enabled them to notice the seven companies that suddenly started a massive (and obvious if you were looking) billing spike. The Post and the Times reporters interviewed Clif Gaus, the NAACOS CEO. While NAACOS may have been the first accredited agency to report it, I am sure that many other individuals reported their claims as fraudulent. At the time I did a quick Google search for information related to my transaction, and there were plenty of people who had reported Royce to the Better Business Bureau with similar complaints, many of whom I am sure called Medicare also.

According to the NAACOS analysis, about 450,000 patients were billed for these catheters in 2023. Normally, Medicare gets about 50,000 billing transactions per year for them. This suggests that 400,000 billing transactions like mine were probably paid by Medicare as part of the scheme.

The Washington Post was able to contact the former owner of Royce Medical, who sold their business in 2023. She stated that this was a big problem for her. Even though she had nothing to do with the fraud – it all occurred after the new owners took over – customers were blaming her for the billing.

I know I did the right thing to immediately report the Royce bill to the Medicare Fraud Desk, but the response I got from Medicare was both unsatisfying and frustrating. I told them that I had not ordered the items, and it was almost as if they didn’t believe me. I thought at the time that if I was billed for this, it was unlikely to be a one-off event, and that there had to be a giant pile of similar complaints that were blinking red lights at the agent that I spoke with, who was part of the fraud prevention group. I have no way of knowing. I can hope that when fraud is this obvious, that our government jumps right on it. Which they may have. It’s hard to know.

Now let’s talk about how the news is reported. And mostly, I mean how they draw graphs! It would appear that the NAACOS people sat down with both the Washington Post and the New York Times reporters, explained what they had come up with, and shared the numbers. Here is how each of them drew their graphs illustrating the same data trend.

First, the Times online version:

This is the New York Times version of the NAACOS data, from 2021 to the most recent quarter.

And here is the Washington Post online version:

And here is the version of the same data as shown in the print edition of the New York Times:

The Washington Post wins!! I did not expect this, but ok. They both correctly attribute the underlying data to NAACOS (and yay for honesty in journalism). Both versions correctly show zero-origin axes with appropriate scaling, and correctly label the vertical and horizontal. The Times online version includes dots that are distracting from the message, and leaves you to guess the peak medicare fraud amount. The printed version of the same plot in the Times shows the jump in a way that appears to be way more startling, so I will leave to you which one is the most “accurate.” The Post, on the other hand, uses shading to highlight the message about how out of proportion the billing is, omits the distracting dots without any loss of clarity, indicates the amount (nearly $1 billion), and adds an explanatory text that provides context for the figures.

This leaves me thinking that there are two remaining problems related to Royce billing my Medicare account.

One problem is that even if the money for my order went to Royce, I have no out-of-pocket liability. This gives me, and other older Americans, little incentive to pursue these sorts of claims. The Post journalists were told by their interview subjects that most people don’t read the detailed medical statements they get, allowing this type of fraud to go on longer than it should. Given that I did not experience any out-of-pocket loss because of Royce’s use of my information, was I really a victim? It’s an existential question like the one about a tree that falls where no one hears it.

A second problem is that I have no idea how Royce Medical was able to obtain my Medicare billing identification information. I now read the monthly statements very carefully, looking for evidence of providers that I do not know, or billing transactions that seem unfamiliar.

And you should too.