It is super fun to complain that “all politicians are corrupt” or that “corporations are greedy.” I ran into a news item this morning that offered something specific that our legislators can do to help out with that last one. A report was just released by the Institute for Policy Studies that details the history, status, and current impact of share buybacks. At the end, you can make up your own mind about whether these are good or bad. Stay with me please. (And if you want to read the report that got me falling down this rabbit hole, here is a link to it: https://ips-dc.org/report-executive-excess-2024/).

We are going to have to first go back to the origin story of shares of stock, and only then can we get the sense of what is happening now. (Shares of stock in a company are like superheroes, you know.) After a share of stock comes into being, it transitions from its origin story to the interminable series of endless storylines, which are unrelated to the origin. We will get to those later.

Here is how my dad explained the nature and substance of corporate stock ownership. “When you own a share of stock, as a shareholder you become an owner of the company that issued it,” he told me. “You participate financially in the long-term success of the company, and you get to vote on important issues at the company’s annual meetings. As long as you own the share, the company is obligated to you as an owner, and they share in any future profit by issuing dividends.” This seemed unlikely to me, but I wanted to know more. Could you lose your money?

“Glad you asked,” said Dad. “Should the company fail and go bankrupt, your share will become worthless; it only has value to the extent that the company is successful. Also, if they have no profit, then they won’t issue dividends.”

In a nutshell this the “origin story” of shareholding.

There are three basic steps in this origin story of being a shareholder:

1) the company needs money to grow. They get much of that money by selling shares of stock. Let’s say that they sell 100 shares at $100 each, giving them, in this example, $10,000 to enhance the value of their company.

2) In exchange for the $10,000, the company issues 100 pieces of paper called “stock certificates.”

3) As long as the company is financially successful, they pay each shareholder a part of their profits in the form of a dividend, paid quarterly. The amount of the dividend is as good as you could get (or better) had you invested the money in something else, like a bond. Plus, there is the upside of long-term price appreciation.

This is a pretty good deal for everyone; the company gets to build a new factory (or whatever is needed for growth), and unlike a loan, they don’t have to pay the $10,000 back that they got from selling shares of stock. You aren’t loaning them the money; you are buying the company. They do have an obligation to pay dividends (according to my dad), because if they didn’t, no one would buy the shares of stock in the first place.

In my dad’s telling, the sequel phase of endless storylines is pretty simple: there is an open market for these stock certificates so that the shareholders can sell their shares to someone else if they want to, making it more likely that people will buy the initial shares, which is what the company needed for growth. Subsequent owners get the same benefits as the original ones – a chance for growth, dividends, and the ability to sell if things change. They are not investing in the company, but are buying someone else’s investment obligation.

The price of the shares on this market depends entirely on the buyer’s perception of the future of the company, as my dad went on to explain. If the company is well managed and has a product for which there is a future, then they would be willing to pay more for the shares. If the company is not doing well (for example, not profitable, in what is now a bad market, or some other trouble) then the buyers would offer less. In other words, the long term price of the share would track the long term management skills and financial health of the company itself.

The sequel phase was famously described by Benjamin Graham in his 1949 book “Intelligent Investing.” Graham felt that the intrinsic value of a company could be measured independent of the share price using the formula below, and he termed the approach “value investing“:

Pretty cool! If “V” turned out to be higher than the current share price, you should buy. Conversely, if the other way around, then sell. Warren Buffett became one of the richest men in the world by following this formula.

Stocks were largely traded during the 1950s and 1960s using the value investing approach. Most large American companies were prosperous and their stock prices tracked with their intrinsic value. My dad did very well, mostly by picking shares of stock from companies that were well managed but underpriced. He looked for low P/E ratios, in Graham’s model.

However, this rosy picture started to cloud up somewhere around the 1970s. US business leaders began to change their attitude after learning of Milton Friedman’s philosophy of the free market. Friedman was a Nobel-prize winning economist at the University of Chicago who popularized the theory that the purpose of a company was to make money for its shareholders, and that any other obligation undertaken by the management was tantamount to socialism and therefore un-American. Following the publication of his widely read book making this argument, he wrote a well-read article published in the NY Times on September 13, 1970, which I quote here:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”

This notion that it was wrong to consider any goal other than making more profit on behalf of shareholders was known as “Maximizing Shareholder Value.” Executives immediately fell in love with it, as it was both easy to understand and it made them personally wealthy. You can see from the chart below that soon after, US business leaders of publicly traded corporations stopped returning profits to employees.

Up until the early 1970s, when US publicly traded companies made a profit, the management typically invested their good fortune in the employees, the facilities, and the products, with a reasonable share given back to the shareholders in the form of dividends.

With the advent of the adoption of “maximizing shareholder value,” this changed, and pretty dramatically. Profits were going somewhere else, and the success of these US publicly traded companies was not being shared with employees or reinvested.

How did this happen? Notice in the Benjamin Graham formula above that a key factor in measuring the long-term value of a company was the term “P/E.” This is the ratio of the stock price (“P”) to the earnings (“E”), or stated another way, earnings per share, abbreviated EPS. ‘Earnings’ is another way to express the companies’ profit, or money left over from selling products after all the bills are paid. So, EPS is the ratio of the profit to the number of shares of stock. As the EPS goes up, the value of the company goes up. Investors and executives realized that this single number was easy to calculate! We love simple numbers!

So, a consensus formed around using EPS as a way to evaluate and pay the executives. If the managers of a company can make EPS go up, then they must be increasing the value of the corporation, which is fantastic and very easy to understand. The pay packages of the executives started to change to reflect “increased EPS” as part of the criteria for a raise.

American executives are really, really, smart and so they quickly figured out that EPS can go up in one of two ways, by either a) increasing the profit, or making the numerator larger, or b) reducing the number of shares of stock, or making the denominator smaller. They are mathematical geniuses.

So, what to do? How about spending some of the company’s money buying back the shares of stock itself, thereby taking them off the market, and making the ‘Share’ part of ‘Earnings Per Share’ smaller? They have already spent the $10,000 from the initial sale of the shares (see my example above), so the cash will have to come out of what otherwise would be profit or perhaps investment in growth, but whatever. Voila! It’s wonderful.

When the buyback strategy started to be considered in the 1970’s there was only one problem: buying back shares to boost the EPS was illegal. Oh, crap! The practice was considered to be a form of market manipulation. That is, it artificially increased the price in a way that is subject to abuse. After the great depression of the 1930’s, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the SEC, was put in place to ensure that America never went through the breadlines and hardship of this era again. Among its many actions, the SEC made this sort of stock price manipulation illegal. They were trying to prevent the speculative excesses of the 1920’s that led to the 1929 market crash.

But again, American corporations had a friend in a high place – this time it was Ronald Reagan. Under his administration in 1982 the SEC passed rule 10b-18, which effectively made stock price manipulation via buybacks legal again. Just like in the 1920’s. Since then, the practice has blossomed.

Like many things, buybacks might be fine in moderation. But here is a quote from a Harvard Business Review paper by William Lazonick in 2014:

“Consider the 449 companies in the S&P 500 index that were publicly listed from 2003 through 2012. During that period those companies used 54% of their earnings—a total of $2.4 trillion—to buy back their own stock, almost all through purchases on the open market. Dividends absorbed an additional 37% of their earnings. That left very little for investments in productive capabilities or higher incomes for employees.”

In other words, 91% of the profit of most of the S&P 500 publicly traded companies went towards shareholders, and therefore was not available to increase employee compensation, improve benefits, make better products, invent new ones, build new factories, make products that don’t break, or whatever. It went into the pockets of the shareholders.

And who are these shareholders? In this same HBR paper, Lazonick notes that the 500 highest paid executives of publicly traded companies made 83% of their compensation in the form of stock awards or options. So, the people who run these companies are highly incented to have the stock price go up. When the stock price goes up, so does their pay.

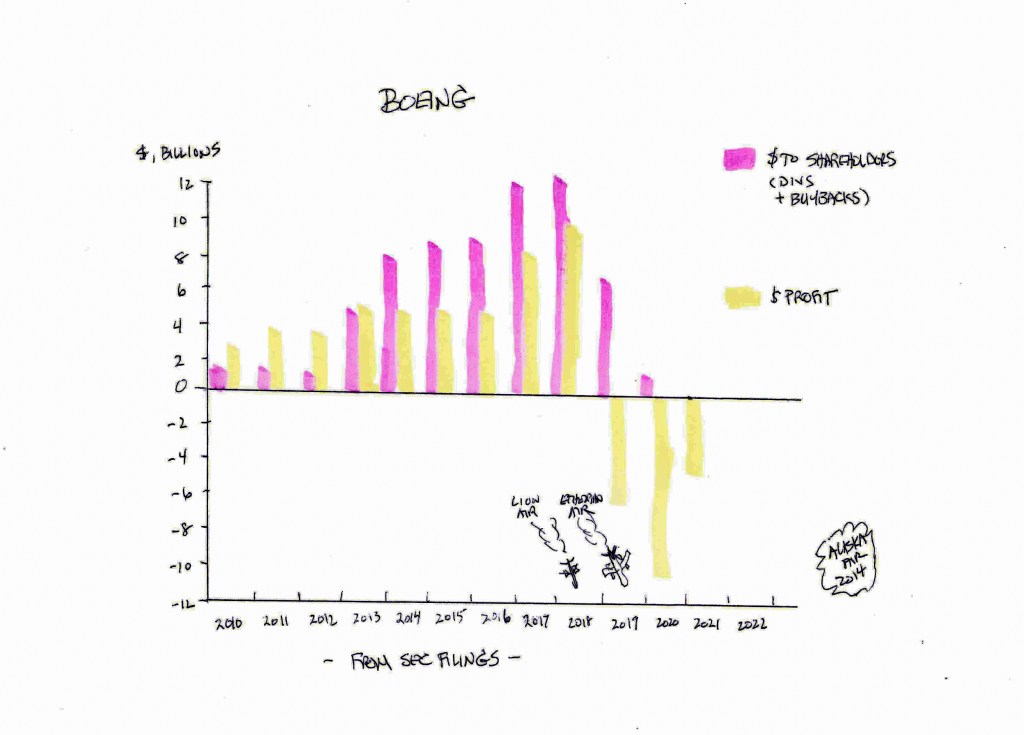

This probably all seems pretty abstract, so to illustrate how maximizing shareholder value can work out in real life, let’s look at the Boeing Corporation. I’m sure that you have heard about the trouble they have gotten into over the two 737-Max planes that crashed in 2018 and 2019, not to mention the door that fell off one of their planes shortly after takeoff this year. I have pulled the cowling off of their corporate finances a bit to see if share buybacks could have played a role. My analysis is shown below in Figure 1.

I did an earlier blog post about their manufacturing issues regarding ‘traveling parts’ at Boeing. If you want to go back to it – here is the link: https://grandpadave.blog/2024/03/21/word-o-the-day-traveled/.

Figure 1:

The pink bars represent money spent on shareholders, in billions – I added dividends and buybacks together. The yellow bars are net earnings, or profit, as reported in their SEC annual filings. In 2013, virtually the entire company profit was spent buying their own stock back. Several observations emerge from this analysis:

- Shortly after Boeing dramatically pumped up share buybacks, they had two catastrophic product failures where customers died;

- After the plane crashes in 2018 and 2019, customers held back orders for future purchases, and their profit went big time negative;

- Up until 2012, shareholder payments were almost entirely dividends, and formed a fraction of profits (I didn’t break this out in the chart, but this is what happened); and

- Between 2013 and 2019, shareholder payments dwarfed their profits, meaning that they were putting more cash in the pockets of shareholders than they were clearing in profits. You can’t tell from their SEC reporting which part of the company this money came out of, but based on the two very public plane crashes, I’m guessing that product quality suffered.

There is a lot that could be said about Boeing, nearly all of which I will not say in this blog post. (For example, today’s news is that their employees are about to go on strike, presumably because management has not kept worker compensation increasing in line with earlier profits or with the employees’ cost of living.) In the case of this particular corporation, there is much evidence supporting the hypothesis that maximizing shareholder value, and in particular buying back shares of stock on the open market to boost EPS, contributed to the business-extinction level problems now besetting them.

I don’t want to just pick on Boeing. For example, Chevron, which my dad rightly thought a soundly managed company when he bought shares of it in 1960, announced in 2023 a $75 billion dollar buyback program in a year when it made a profit of only $35.5 billion. If there’s anything that has gotten Americans upset recently, it is high prices at the pump. Instead of using their profits to lower pump prices, or perhaps to mitigate global warming, they are giving twice their annual profits to their shareholders.

I am leaving you to judge for yourself whether making share buybacks legal was such a good idea, and whether the goal of a corporation should be to maximize shareholder value to the exclusion of everything else. However, if you agree with me that there is altogether too much of this floating around the corporate boardroom, then you can do something about it.

Right now there is a bill pending in the Senate Finance Committee that would reduce these things. It’s S.413, and it proposes to change US tax code clause 4501(a) to levy an excise tax of 4% on any share buybacks, collectable by the IRS. It won’t stop the practice, but it would help. You can write to your members of Congress! Tell them that they need to get behind this and any other similar legislation. I know there is a lot of noise right now about the election of the President, but it is not the President’s job fix this problem – it is the job of our Congress.

So light a fire under them. If I were running for office I would make this my campaign slogan, perhaps printing it on the front of red baseball caps:

MAKE BUYBACKS ILLEGAL AGAIN!

Do you think it would catch on?